- Home

- David McPhail

The Years Before My Death Page 8

The Years Before My Death Read online

Page 8

I had no doubts about my decision. What was doubtful was how I was going to survive. I examined the possibilities. Although the other local newspaper, the Star, and The Press were rivals there was no prospect of a job there. The editorial staff probably had the same opinion of an uppity young man who’d treacherously jumped ship. The only option was radio and this would require me to make a major readjustment. As a newspaper reporter, like my colleagues, I looked down on radio journalists. We sneered because they had so little to write and as their copy disappeared into thin air and wasn’t enshrined in print they didn’t really have the right to call themselves journalists. But, they made money and an unemployed newspaper reporter didn’t. So I made an appointment with the head of the Christchurch newsroom, John Cockerill. This skinny, cheerful man surprised me immediately. I had brought along a scrapbook of my newspaper stories. He dismissed it with a wave. ‘I don’t need to see that stuff,’ he said. ‘When can you start?’

I replied that was really up to him.

‘How about tomorrow morning?’

I was flabbergasted. I hadn’t even expected an offer. ‘That would be fine,’ I spluttered.

‘Right, see you about ten o’clock,’ he said. ‘Oh, and don’t forget to take your scrapbook.’ It was the shortest interview I’d ever had in my life.

So, I became a radio reporter. At this time people speaking on radio had their voices graded. If you were an A you could be used at any time on any show. A B-grade restricted your areas of performance slightly and so on down to D. With my recurring stammer I worked out I was probably graded H and could only be used on-air at a time of national disaster when everyone else was dead. But, the change to radio was exciting and I became friendly with another young journalist, John Steele. Our stories were rarely longer than three paragraphs but we had to generate a lot of them to fill the daily bulletins.

One Saturday, John Steele and I were the only journalists on duty. Christchurch was as quiet as a graveyard. There was simply nothing happening. John Cockerill was always adamant we found our own stories. He didn’t approve of following up pieces that had already appeared in the newspapers. I was becoming frantic. A midday bulletin was approaching and we had virtually nothing to report.

I was checking the Christchurch Central police watch room again and praying for a gory crime, when John Cockerill strolled in. He was just passing and decided to see how we were. John Steele and I explained our dire position. John Cockerill let out a soft whistle and said, ‘You do have a problem, boys.’ Then he sat at a typewriter, banged out seven stories without checking a note and walked to the door.

‘How did you know all that?’ I asked. He turned and tapped his head with his finger. ‘Always keep something in reserve, boys.’

On another weekend John Steele and I were listening to the police radio in the hope of uncovering a major crime story. We heard that officers were moving in to watch a house on Latimer Square. This could be it! The square was almost next to the newsroom but we agreed we wouldn’t walk. It might attract attention. So John and I jumped in the newsroom’s car — a small, green Ford Anglia — and began driving around the square. We didn’t see a thing: no police cars, no constables. After 10 minutes we drove despondently back to the newsroom and listened to the radio again. Then we discovered the officers in the square were reporting a green Anglia had been driving suspiciously round and round for about 10 minutes. So, they decided not to make any move on the house they wanted to observe until it had gone.

I was alone in the newsroom one Sunday night when Anne and John burst in. They had been to church together, but earlier in the afternoon Anne had heard a rumour at Christchurch Hospital of a dramatic piece of surgery. The rumours suggested doctors had sewn back on a man’s severed hand. John and I jumped on the telephones. It took over an hour to confirm the details but this was the big story we’d always wanted and we’d have never heard of it had it not been for Anne. The next morning we listened to our story on the BBC World News.

There were changes coming and the line between radio and television news blurred. Our newsroom shifted to a new building and increasingly I found myself sub-editing television news items. After a year, the change was complete and I was working as a full-time television reporter. The medium was fairly primitive. At this time there was no network bulletin and news footage was shot on hand-cranked cameras. When video machines did arrive the tapes were as big as medium-sized suitcases. But, there was excitement as we grappled with the unfamiliar technology and learnt by endless mistakes how to produce comprehensible bulletins.

The new technology was always unpredictable. A move was made to introduce automatic cameras in the small news studio thus removing the need for a cameraman. Early tests were successful but when one was used in Christchurch it developed unusual habits. An announcer was speaking when unexpectedly the camera started panning away from him. There was consternation in the control-room but the camera continued to move. Showing great presence of mind the announcer, George Taylor, started leaning out of his chair in an effort to keep his face in sight of the camera. George leaned until he was actually out of the chair and was following the camera on his knees. Then, someone in the control-room must have hit the right lever because the camera stopped and suddenly whipped back to reveal an empty chair. Seconds later, George slid uneasily on to the screen and, after clearing his throat, continued with the bulletin.

I worked with many talented and immensely likeable people during the late sixties. Two have remained life-long friends — Murray Reece and his brother Simon. Murray was a cameraman and Simon a film editor. Through them Anne and I met the redoubtable, unbelievable and unforgettable Margo Sutherland. To fully convey the dominance of her personality, I need to describe her. She was huge. One evening when I drove her home, in a pretentious convertible car I’d just purchased, she broke the springs on the passenger’s side. Margo’s colossal size was due to a medical condition that was never mentioned or treated. She was articulate, wildly erudite and had many friends. Margo’s voice was elegant and provocative. I often wondered about the reactions of pale young men who had heard her musky fervour over the telephone and then encountered this huge person in the hallway.

I liked Margo. She was a film editor and when I first started making reports on television she would carefully and tirelessly edit out all the stuttering conundrums of my stammer. Many years later, I was standing at a pedestrian crossing in Auckland. A silky, sensuous voice spoke to me. I turned, somewhat surprised because women with those voices hardly ever speak to me, and a slight, elegant woman was standing behind me. I recognised her but was uncertain. It was Margo Sutherland. We spoke briefly. She had reversed her obesity by an operation, favoured by the late David Lange. Her stomach had been stapled. She spoke to me in the same suede tones of long ago. Then, I realised something was wrong. Margo had had a grandeur because she was large. Now, reduced to the dimensions of an ordinary person, she had lost her presence and few people paid attention anymore.

In late 1967 I had a meeting with producer Des Monahan. He was in charge of an increasingly successful local magazine show, Town and Around. The nightly programme was hosted by the engaging Bernard Smyth. But, its main feature was the presence of a bitingly intelligent and incisive interviewer named Brian Edwards. Des wanted me to leave the newsroom and join Town and Around as a reporter. This offer was totally unexpected. Certainly, I’d watched with admiration and a little envy as Town and Around and its team captured a growing audience, but I knew there were other reporters in Christchurch whose credentials were more solid than mine. But, Des was energetic, enterprising and persuasive. I considered for at least 10 seconds and said, ‘Yes.’ I joined the programme the following year.

From the start Des encouraged Brian and I to attempt more light-hearted pieces. Des was a gifted producer, finely attuned to current affairs but with a broad sense of humour and a bellowing laugh. Brian too had a sharp wit and together we produced some ‘light-hearted’ pieces. The a

udience’s reaction was muted but I realised how much I enjoyed performing this material. Later that year, Des and Brian left Christchurch. They would reunite in 1969 on the highly influential current affairs programme Gallery.

I continued trying to develop my skills, not as a fierce interviewer but as the presenter of quirky, slightly odd stories. My regular assignment was to travel to the West Coast for one week every month to dig out local stories. I had originally been dispatched to the coast to placate viewers who’d been enraged by a piece Brian produced earlier. After spending a wretched week in heavy rain with little chance of filming anything, he stood on a beach and delivered an incisive and pitiless assessment of the West Coast and its weather. There was only one television channel in New Zealand then and viewers were highly sensitive to anything that might be said about their particular town or region. They were also possessive about what they felt was ‘their’ channel. The coasters went crazy about Brian’s forthright appraisal and it would have been foolish and probably dangerous to send him back. So, I went over.

One of my first discoveries was a wonderful practical joke that had been perpetrated years before. At that time, there was considerable talk about the possibility that moa might still survive in the more remote parts of Fiordland. Ornithologists dismissed the speculation as nonsense. Others, less qualified, felt that while it was unlikely, the possibility shouldn’t be ignored. A man called Mick Neville decided to end the debate once and for all. I probably heard about Mick in the bar of the old Recreation Hotel in Greymouth, which was my main source of unreliable information at that time. I drove down to Kumara to speak to him. He was wary, but most West Coasters were a little cautious around ‘jokers from the television’, especially after Brian’s broadside. When I asked him about moa sightings he gave me an odd glance and said, firmly, ‘Don’t know anything about that.’

So, I left it, but over the next few months I’d sometimes visit Mick and raise the question again. His reply was always the same, ‘Don’t know anything about it.’ On my last visit I was walking to the camera van when Mick’s wife came down the path holding an old pair of boots. Immediately I went back into Mick’s house and told him I’d be under the road bridge over the Taramakau River at 8.30 am the next day with a film crew. I would wait an hour and if he didn’t arrive I’d drive off and wouldn’t bother him again. My friend, Murray Reece, was the cameraman, and we speculated at length about whether Mick would turn up. We shouldn’t have wasted our time. At 8.30 sharp, Mick arrived on his bike with a moa head and neck made from a punga tree under his arm. He was also carrying the boots. They had been the key.

Mick thought the ‘moa in Fiordland’ story was a bit of a joke but it had given him an idea some years earlier. He got some wood and on his lathe turned two sets of bird’s feet. He nailed the feet to the soles of a pair of boots. Then, he hammered six nails into the tips to represent claws. The following evening he cycled down to the Taramakau riverbed and found a wide patch of sand near the bridge. He put on the boots and taking large strides stamped around the sand. The result looked remarkably like the prints of a very large bird.

Next morning, Mick contrived to walk over the bridge with a friend and his friend spotted the prints. There was consternation. Reporters and photographers from the Greymouth newspapers rushed to the riverbed and over the new few days excited stories appeared. Eventually, according to Mick, the government ornithologist, a Dr Robert Falla, arrived in Greymouth to study the find. Dr Falla was unimpressed. He was curious about the prints but there was no sign of habitation. Nothing to indicate a large bird lived in the area.

As he was explaining all this to me Mick was stomping around the riverbed in his moa boots. He stopped and said, ‘You want habitation, Dr Falla? I’ll give you habitation.’

I asked, ‘What did you do?’ Mick returned to stomping and replied, ‘I went home, got some chicken shit from the fowl run, mixed it with grass clippings and shoved it through a mincer. Then, I got an old stocking of the wife’s, filled it with the mixture and made a hole in the bottom.’ He then cycled back to the riverbed with the stuffed stocking and a pair of lawn edge clippers tied to the back of his bicycle. Mick put the boots on and stamped around the sand squirting small coils of the mixture onto the ground.

Satisfied with that he stamped over to some trees beside the riverbed and attacked the leaves with the edge clippers. ‘This is habitation, mate,’ he told me. The story became a little vague after that. There were suggestions Dr Falla returned, took casts of the footprints and died believing the last known moa was living on the Taramakau riverbed in 1947. However, nothing Dr Falla wrote made any mention of this. But then Dr Falla’s writings are hidden in libraries. The moa story was alive and well in the bar in Haast.

I grew progressively wiser as I drove up and down the West Coast. With my camera crew I ended one day at a bar in Hokitika. We hadn’t shot anything and I was becoming rather desperate. I asked if there were any interesting stories about Hokitika. It shows the extent of my naivety that I even asked the question. The boys peeled off from the leaners and gathered around. One particularly grizzled man asked, ‘Would you be interested in the black bears?’

I swallowed the hook. ‘What bears?’

He started a detailed story about a Chinese man, named Ah Fong, who travelled the West Coast goldfields with two trained bears. They performed tricks and one could even balance a glass on its nose. I had my reporter’s pad out and was scribbling notes. I offered to buy the next round. There were 13 men in the next round. ‘What happened then?’ I asked, fidgeting to get money out of my pockets.

With the easy charm of a teller of fairy tales he went on. ‘Ah Fong got into a card game and was shot for cheating. No one knew what to do with the bears, so they let them go and they raced off into hills. The bears bred and they still live there.’

I snapped my reporter’s pad shut. ‘So what happened next?’

He looked at me and smiled. ‘Well, I won’t know until you’ve bought the next round.’ They were still laughing when I slunk out of the bar.

One morning in May, 1968, I was asleep in the Recreation Hotel in Greymouth. The film crew and I had scratched together five middling stories and planned to drive back to Christchurch that morning. I remember sensing a jolt. I thought it was either a dream or a nightmare. Then, I woke up. The bedroom was shaking and the chair beside the bed, with the alarm clock on it, was jumping up and down. There was a strange combination of sounds — a roaring that was suddenly overwhelmed by a thunderous creaking. ‘Jesus Christ.’ I didn’t realise it was an earthquake until I reached for the door knob and it was moving. I rushed out into the corridor and started running around in circles. The hotel was bucking and rearing like a fairground ride. I ran down the staircase and suddenly realised I was in the building’s most vulnerable spot: the stairwell. So I raced back up the stairs and started screaming, ‘Get out, get out. We’re all going to die.’ I’m not very good in emergencies.

The Recreation Hotel was an old wooden building that swayed and flexed with the tremors. It creaked and groaned but it didn’t fall down. After the film crew had calmed my hysteria we all went down to the kitchen. The wife of the owner had stoked up the coal range and was cooking a huge, greasy breakfast. ‘You need a good lining on your stomach to face days like this,’ she said.

This was the morning of the 7.1 Richter scale Inangahua earthquake. If the jolt had hit a more populated area it would have been a disaster. For some, it was still a tragedy. We were the only film crew on the West Coast but, fortunately, the telephone lines were down so I couldn’t receive screaming instructions from news editors up and down the country.

As we walked through Greymouth we could see little major damage. There were mainly crowds of alarmed and disorientated people. Although we did discover one story that was both poignant and funny. Japan’s national Rugby team was touring New Zealand. The players were due to meet the West Coast team on the day of the earthquake.

In a

creaky hotel, the 12 Japanese players were asleep in beds on a veranda above the footpath. When the earthquake hit the floor fell. The players and their beds hit the footpath below. No one was hurt. ‘Just like back home,’ said the manager.

I hired a small aircraft to fly us back to Christchurch with a side-trip up to the Inangahua Junction to film the worst of the earthquake. It was an alarming flight. The landscape was buckled and twisted and near the junction we spotted a landslide that had killed two women. I remember one story I could never confirm. A taxi driver was heading home. At 5.24 am he approached a bridge. As the earthquake shook, the road in front of him dropped and he slammed into the bridge. You can’t feel an earthquake when you’re driving a car.

In the years leading up to this time I became more deeply in love with Anne. She had a beautiful face, an unpredictable manner and a determination that produced both admiration and alarm. We seemed a likely match but I was forever doing things she thought were immature. One Friday night we delved into a number of jeweller’s shops. At one, we mischievously ordered an engagement ring. I loved the secretive intimacy and romantic daring of this escapade. But by Sunday I was thinking seriously about the implications of engagements and marriage and on Monday morning I telephoned the jeweller and cancelled the ring. Anne refused to speak to me for a fortnight. Our relationship continued to be volatile. For periods of time we were apart, but the rather impulsive passion we had for each other was fuelled by another, less obvious, factor. We had both suffered from disruptive childhoods and had decided that our futures and, perhaps, our family would not be a repeat of our early lives. We married in 1967.

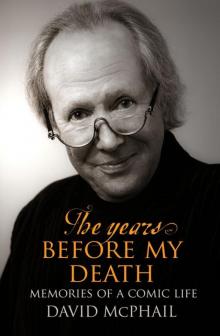

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death