- Home

- David McPhail

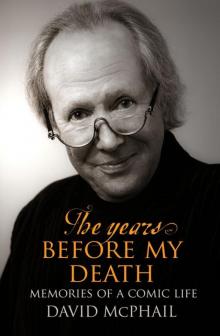

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death Read online

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Before I Start

1 Beginnings

2 Learning to Grow

3 Songs

4 Afterlife

5 Men and Boys

6 Chinese History and Other Diversions

7 Plays, Beers and Santa Claus

8 The Real World

9 A Toe in the Pond of Comedy

10 Tottering towards Laughter

11 Now We are Four

12 New Times, Terrors and Odd People

13 ‘Something To Look Forward To’

14 ‘A Week of It’

15 A Deep and Funny Friendship

16 Nightclubs and a Prime Minister

17 Right Royal Occasions

18 Travelling On

19 Trials and Tribulations

20 Inside the Glass Tower

21 The Show that Started with a Letter

22 Allegations, Innuendos and Videotape

23 Into the Spotlight

24 From Fame to Frailty

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Plates

Copyright

THIS IS FOR ANNE, WITHOUT WHOM NOTHING WOULD HAVE HAPPENED

‘I think it’s the duty of the comedian to find out where the line is drawn and cross it deliberately.’

· George Carlin ·

Before I Start

Many people mark their lives by associating them with a point in human history. Where were you when John F. Kennedy was shot? I was asleep. What were you doing when his brother Robert was killed? I was asleep. Martin Luther King: the same. I have slept through most of the major assassinations and historic events of the twentieth century. I think that’s quite an achievement for a man who doesn’t like going to bed.

There is a dictum that a memoir should never be published until everyone in it, including the author, is dead. I couldn’t wait that long. But, in deference to anyone appearing in these pages, this book is the product of memory that can be imperfect, ill-defined and as reliable as a horoscope. These are the accumulated seeds of my life thrown with a handful of unreliable fertiliser onto a very large field.

So, I start at the end. Then, we’ll know where we’re heading. I’m not middle-aged anymore and when that happens strange sepulchral shapes and memories start gathering in the corner of old rooms. Like anyone who hears the tolling of the years, I start thinking of hour-glasses and sand and dust and finally ashes. I shall lay my cards down. I have been married for over 40 years to a woman whose love exults me. I am the father of two children whose lives enchant and redeem me. Their new loves, Sarah and Matthew, perplexed then captivated me. I have four grandchildren whose beautiful existence may actually provide the reason for my life. These are my proudest achievements and listing them might seem an appropriate way to end a book, not start it. But you are not getting away that lightly.

Chapter 1

BEGINNINGS

It is April 1945, the month and year of my birth. My continuing existence confirms I must have been present. Whether I enjoyed the experience is not recorded. Evolution is perplexing. You never remember the first moment of your life and you’ll never remember the last. I recall nothing of my early life but faded photographs suggest I was a small, round-faced, somewhat solemn boy who climbed trees and sat on the bonnets of cars. As I grew older I didn’t change much. A month after I was born, Adolf Hitler blew out what remained of his brains and Germany surrendered. Try as I might, I have failed to establish any link between my birth and those events in Berlin.

I remember there were tramcars on Bealey Avenue in Christchurch and I could hear their bells jingling in the evening. The Second World War had just ended and food was rationed. This euphemism meant you couldn’t get what you wanted to eat. So, my mother preserved eggs in brine and packed them into 10-gallon kerosene tins. When the eggs came out they tasted of brine and kerosene. My mother boiled the eggs proudly and I ate them unhappily. Later, I heard of a regulation — any tins used to store preserved food could not be reused to carry kerosene. I wondered about my mother’s eggs and their place in the toxic market.

There was silence at night in the late 1940s with only the occasional back-fire of a badly tuned car. It was so quiet that in autumn you could hear the leaves leaving the trees. There were not many cars in Christchurch and, apart from my father’s comical Ford Prefect, most were Chryslers or Pontiacs; huge American cars with grinning chromium grills that were carefully locked in garages at night, ready to dazzle the neighbours in the morning.

There is a common belief that the fifties in New Zealand were drab. Those who insist on this idea didn’t live where I did. Everyone walked: men with umbrellas and pipes, and women wearing noisy heels, draped in fox-furs. I should explain this fashion. The body of a dead fox, complete with its head and tail, was carried elegantly over the slim shoulders of a graceful woman who was, most likely, smoking a cigarette on the end of a long holder. Both men and women wore hats. There were four milliners within five minutes of Cathedral Square. And, two hatters as well. I knew because my father bought hats from both of them.

On Saturday afternoons, looking across Lancaster Park as the gas works belched white clouds of God knows what into the silent air, I remember two things. Certainly not the game. It was probably Albion versus Sydenham and if Sydenham lost we were in for a long tirade about the girlish antics of the front row. What I recall is an embankment filled with hatted men and a cloud of blue cigarette smoke floating motionless above them. Then, the long walk back to the tiny car and my father’s eccentric driving.

There were nearly as many tobacconists in Christchurch as there were hotels. I was never sure how many hotels, but later in my youth I discovered, in something of a stupor, there were roughly 20. Then, it was called a ‘pub crawl’. Now it would be described as an ‘after match function’.

My father’s favourite tobacconist was Finney’s. They had a store on High Street and later one in Cathedral Square. Cigarettes, which are now the despicable tools of the Devil, were then accessories to social refinement and indicators of a raffish or slightly wanton view of the world. You smoked a cigarette, not for the nicotine, but for the way it made you look. The nicotine came later. Would Humphrey Bogart — and remember his name was Humphrey, not Clint or Chuck or Tom — have been such a magnetic and memorable figure if he’d played the role of a samurai Scientologist with Mount Taranaki in the background?

Of course not. He had a long cigarette drooping from his lips. The smoke was getting caught under the brim of his hat. It was the beginning of a minor thunderstorm. But Bogie didn’t care. And he didn’t say, ‘Play it again, Sam.’ He just said, ‘Play it.’

The Health Department can put the viscera of dead animals on cigarette packets and remind us that men, never women, can become impotent. But Sir Walter Raleigh’s legacy is hard to extinguish.

Strangely, my first glimmerings of memory come not from my mother but from my father. Ivy Freda Halford was my father’s second wife. They had met years before my birth under curious circumstances.

Alexander Edward McPhail was the chairman of the New Zealand Rugby Union. Although he lived in Christchurch he travelled frequently to Wellington for union meetings and it was in the perfume department of Kirkcaldie & Stains that he met a petite, lip-sticked young woman with braided hair tied across her forehead and a notable bosom. My mother, who was always fiercely circumspect about her age, was in her late twenties at the time. My father had been born in 1881. I know this because I’ve still got his passport. It is a heavily embossed document in English and French. There is a long preamble from the Governor, Viscount Galway, finishing with the commanding words:

/> I request and require in the Name of His Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford him every assistance and protection of which he may stand in need.

My father’s age and the time to which he belonged had an acute effect on my life. In two generations, my history spanned over 120 years. My father was born the year Tsar Alexander II was assassinated, the same year the gunfight took place at the O.K. Corral. This was the year Sherlock Holmes first met Watson in the novel A Study in Scarlet and workers started carving out the Panama Canal. As I grew up I had the odd feeling that, through my father, I was somehow linked to the events of a vast and distant past.

In a search for some connection with my own history my wife Anne and I drove to the Woolston Cemetery in Christchurch. It was a blustery day and the dead leaves of old oak trees were being confused by an autumn wind. This is a small cemetery surrounded by factories and dull houses. As Anne and I entered, a man walking a greyhound watched us with hooded suspicion. I regarded his dog with equal distrust. I knew why the man was uneasy as old cemeteries are forgotten places. People don’t visit the long dead. Hemmed in by the thundering present, the tombstones looked artificial, like props from a low-grade horror film. Then, we saw the names: James McPhail, who died 9 June 1905; beside him, Anne McPhail, his wife, who died 17 July 1920. They were my grandparents. Not far away was the grave of Margaret McPhail who died at the age of one in 1886. She would have been my great-aunt.

Her name was chiselled beneath the names of John James and Ada McPhail, my uncle and aunt. Curiously, Aunt Ada died in 1968 when I was 23. The gravestone was my first and only meeting with her. Her name had never been mentioned to me.

Underneath Margaret’s name was another: Leonard Thomas McPhail, who drowned accidentally at Wimereux in France just two months after the First World War ended. He was a member of the 8th Otago Regiment and was 24. He was also an uncle. There is nothing to suggest how he drowned (during a later war some exuberant New Zealand troops went swimming in vats of wine). It was as if these old hostages of the past were rising to embrace me. So I moved away.

It was cold when we left the cemetery. The lifeless oaks were trying to attract attention by waving at the wind. But, no one looks at old trees or crooked tombstones. Cars were growling up Ferry Road. There was the occasional squeal of a wheel spin.

Outside the cemetery there was neither sanctity nor silence. I didn’t expect it. We’re living in a world where memory describes a computer’s capacity, not the sum of human life. I left the graves of my unknown ancestors proud that I shared their name and saddened I had never known them.

I think Alexander Edward McPhail met my mother around 1936 making him 55 and she, as mentioned earlier, probably in her late twenties. The difference in their ages provoked disapproving whispers and, although a romance between a young woman and an older man was never discussed publicly over afternoon tea and sardine sandwiches, it was perfectly proper to condemn this wickedness behind the cover of a velvet glove. The next time my father visited Kirkcaldie & Stains, Freda had dropped the ‘Ivy’ from her name that she detested — as in ‘clinging ivy’ — and was now working in the jewellery department. In later life, whenever my parents discussed their courtship, which was rarely and always in guarded language, much emphasis was placed on the extraordinary coincidence of their meetings. What was never explained to me was why a man in his mid-fifties would spend so much time hanging around perfume and jewellery departments were it not for the presence of Freda Halford. But it was not only the difference in their ages that gave rise to speculative gossip about my parents.

My father had four children by his first wife and the eldest, my half-brother Clem, was only a few years younger than my mother. This was a romance that stretched the rigid social conventions of the time. However, as I was to discover, my father was strong-willed and stubborn and my mother high-spirited and, in spite of the surprise and dismay felt by my siblings, the marriage went ahead.

My parents had been married for seven-and-a-half years when I was born. My father was 63. In later life I was to marvel at his stamina. Let me describe him. Alec McPhail was a man of modest height with clear blue eyes and receding white hair. He had a resolute jaw with the jagged lower teeth we have all inherited. My father was one of ten children who lived in a small house near the Heathcote River. He once told me the family swam in the river ‘to amuse ourselves and get clean’. His father was a shepherd who had emigrated from a small Scottish village named Caerdon and my father named his home after the hamlet.

I was told that, once, a relative — an uncle, a cousin or someone related — travelled from London to the Scottish border and then boarded a bus for a three-hour ride to this remote community. The only street was deserted but McPhail noticed lace curtains flicking in the silent windows as inquisitive eyes surveyed the stranger. Near the ancient Kirk he found an elderly man and asked about the McPhails. The man dropped his head and in a quiet voice replied, ‘Och, they were a bad bunch.’

Equipped with this unsettling knowledge, McPhail entered the church and asked the sexton if he could see the parish register. The sexton was delighted and led my relative to the antique book. It was then the sexton made a fatal error. He turned and said, ‘There is of course a charge to look at the register.’

McPhail’s face darkened. ‘A charge? How much?’

The sexton smiled. ‘Only ten pounds.’

At the mention of money McPhail turned, left the church and the village and travelled all the way back to London. If his visit did not achieve much, it did at least prove we came from Scotland.

I know nothing of my grandfather. He and most of his children had died before I was born, but I was named after one of my long lost uncles, David McPhail. He was, according to legend, a humorous, if somewhat dissolute, character. You may draw any connections you wish. In his early life David had been a successful athlete. Then, for the McPhails, he made an unforgiveable error. He decided to play Rugby League. This generated the same ringing condemnation a conversion to Roman Catholicism would have produced. From that moment on, David was always called Davie. He left New Zealand and played professionally in England for the Wigan club. On his return, rather than being ostracised by an enraged family, he was given a significant task.

During the journey from Scotland, one of my grandfather’s brothers had decided to stay in New South Wales. With some financial help from his father, he had acquired a large piece of land at a place called Sale. This had created some discord in the New Zealand family who felt a sense of ownership in the property. Davie was selected to cross the Tasman Sea and demand the eponymous sale of part of Sale to recompense the family. The McPhails have never been known to approach a problem with diplomacy when a full-frontal attack is possible. It was rumoured the Australian government was interested in Sale as a site for a new air force base and Davie was instructed to be forceful.

The details of his Australian sojourn are sketchy but family tradition suggests his propensity for a ‘bit of a drop’ played a part in the negotiations. On his return, and after consuming a few drops, Davie announced assertively that the family would not get a ‘brass razoo’ from the sale of Sale. Someone asked why he hadn’t been more aggressive and uncompromising, clearly forgetting these were two characteristics Davie simply didn’t possess. As the arguments mounted and the shouting got louder, Davie defended himself by saying there was one piece of good news. The old uncle had sent everyone his best regards. Remembering the event, my father said he was surprised Davie hadn’t brought back a handsome scroll for giving the land away.

Five decades later I landed at the Royal Australian Air Force base at Sale. I had to restrain myself from falling on my knees in the manner of later Popes and kissing the ground that once might have been mine.

I was a reporter at the time and found myself on the ancestral tarmac because I was to fly across the Tasman in the first United States Air Force Starlifter transport ai

rcraft to land in New Zealand. This huge jet, with ominously drooping wings, would ferry supplies to American bases in the Antarctic. My intention was to make a documentary about the Starlifter and its cargo area, which I was told, with irrepressible enthusiasm, was the size of two basketball courts. Unfortunately air force security decreed I was authorised to see the cargo area or anything of the aircraft, but not film it. There were two exceptions: my own seat and the cockpit. (As a semantic aside, a female pilot recently told me not to use that word anymore. ‘It’s a flight deck now.’)

Once inside whatever it’s called, my view of the glassy Tasman Sea was obscured by the cigar smoke rising from two horizontal pilots who were enjoying the ride. Their feet were placed on the control panel and their caps pulled over their eyes. When we began our descent into Christchurch flying in America’s most sophisticated transport aircraft an anxious young lieutenant tapped me on the shoulder. Above the roar of the engines he shouted, ‘Look out the window. We’re a bit confused. Are those what you people call the Port Hills?’

I panicked immediately. ‘They don’t know where we are!’ I grabbed the lieutenant’s sleeve and yelled, ‘The airport’s on this side of the aircraft.’ Then I squeezed my eyes shut and sat through the most frightening landing I’d ever experienced. As I tottered off the Starlifter I felt a little like Uncle Davie coming home with nothing. Sale had not been good for either of us.

The last I heard of my uncle he was a rent-collector. Apparently, Davie’s most memorable achievement was driving his car along the footpath of a Christchurch street in the middle of the night. At my father’s funeral he’d found himself at the centre of an angry argument. His defection to Rugby League resurfaced as it always did when the cork came out of the whisky bottle. The McPhails had long memories, short tempers and little tolerance. Davie died largely unnoticed and hardly remembered.

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death