- Home

- David McPhail

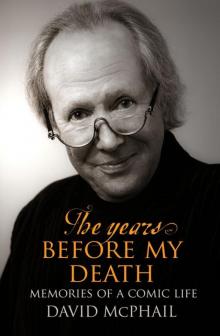

The Years Before My Death Page 21

The Years Before My Death Read online

Page 21

The children were tired and sleepy. Anne was trying to find a way to throw a cigarette out the window and the guide had started jabbering on about the flora of Southern China. There were bigger guns ahead and the stares from the binoculars were becoming more aggressive. I knew we were close to the Vietnamese border and that China and Vietnam had decided long ago to become unfriendly. We were in a dangerous place. I asked the driver to stop.

It was a tricky moment. I had to tell men, whose language I didn’t understand, that we were in the wrong spot. But, I had to do it without conveying to my children we were in danger.

The driver saved me. I pointed to the troops on the hills, he shrieked, swung the van around and drove like hell. The children, who were jolted awake, asked what was happening. I replied, with as much serenity as I could muster, that we were driving quickly because we didn’t want to miss dinner.

The Southern Command of the People’s Army didn’t check our exit visas when we left China and nothing was demanded of us. Matthew, who was very sick, only wanted a glass of clean water. He couldn’t get that until we reached Hong Kong.

Hysterical driving was to become a feature of our travels. Anne and I were in the hills above Palenque in Central Mexico. I’d become almost obsessed with the Mayan civilisation and I needed to see the remains of their cities and wanted to have everything I’d read confirmed by touching their stones. Anne was far more sensible. ‘Ruins are ruins are ruins.’ She was right. The Mayans, for all their erudition and sophisticated architecture, vanished. They might have devised the most meticulous, mathematical systems and capped them with astronomical predictions, but in the wide, flat country of their civilisation only mysterious monuments remain. It is said that a vast meteor crashed into the sea just off the Yucatan Peninsula. The resulting clouds and dust extinguished the dinosaurs and changed the ecological future of the world. It’s a wild claim, but as we drove across the wide and unhappy bracken of the Yucatan, there was a sense that something had definitely gone wrong there.

Before we left the city of Villahermosa the driver asked in mostly incomprehensible English if we would object to three Mexican women joining our tour. These middle-aged women were elegant and voluble. They seemed like entertaining travel companions and they were.

The Mayan city of Palenque rivals most of the world’s more familiar archaeological ruins. It is small and distinctly beautiful. Much of the city remained surrounded by jungle. This beauty could be seen at odds with the descendants of those who built it. They were short with wide, brutal faces, suspicious eyes and mostly worked as waiters in restaurants. Forget the meteor. Something else happened here five centuries ago.

The driver asked if Anne and I would be prepared to divert our tour to a place called Agua Azule so the three Mexican ladies could have a ‘sweem’. This request wasn’t unreasonable and, although it seemed we’d be charged something like forty thousand pesos, I didn’t want to deny the ladies their swim. There was one condition. Anne and I had to be at the Villahermosa airport at 7 pm. The driver raised his arms in cheerful confidence. This would not be a problem.

We started the 100 kilometres drive into the Mexican highlands on a twisting road that kept turning on itself. Children wearing only loin clothes threw sticks as we passed and I was becoming increasingly uncomfortable. This was as far from Christchurch as I’d ever been.

There was a barbed wire fence around Agua Azule. A group of men, from my worst nightmare, stood at the gate. They were either very drunk or demented. One carried a machete. They lurched at or leered into the van. I kept thinking, for God’s sake, we’re just here for a swim. Finally, we passed the checkpoint and the Mexican ladies had their ‘sweem’.

Agua Azule was everything the Mexicans promised. It was a valley of splashing waterfalls and deep pools surrounded by the silence of a green jungle.

Anne and I didn’t swim. I just looked at my watch. I approached the driver, ‘You do remember we have to be at Villahermosa airport at seven o’clock.’ His eyes went wild. He stamped out his cigarette, screamed at the women and started revving the van. So began the most terrifying road trip of my life. I was sitting beside the driver. Anne and the Mexican ladies, who seemed totally unconcerned, were in the back.

The driver became hysterical. We shot down the slalom of that narrow road at 90 kilometres an hour. If any children with sticks had been standing on the edge, they’d have been sucked up in the slipstream.

I kept yelling at the driver to slow down, but he continued lighting a cigarette from the butt of an old one and didn’t seem to notice. When we hit flat land I thought everything might calm down, but this only spurred him on. The Mexican roads were narrow and our driver, who’d been banging his horn at anything travelling under 120 kilometres, would spot a gap and turn into the face of an oncoming Mack truck. He confronted this crisis by simply hammering his horn and flashing his lights. Four times I considered how odd it was that Anne and I would die in Mexico. As we came to a shuddering stop outside the Villahermosa airport the driver turned to me. He smiled and the neon lights caught the glint of his gold teeth. ‘See, señor, you had plenty of time. I promised, didn’t I?’

He had, and Anne and I waited ten minutes before joining the next flight to Merida.

Chapter 19

TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS

Satire can be a perilous way of making a living. For years Jon, Alan and I had written many offensive sketches that taxed the patience of a large number of people. Despite the speed with which we wrote and produced programmes we were always careful with our material. We knew there were limits and there were lines that could not be crossed. Perhaps it was inevitable that the very nature of our writing would, one day, push too hard against the laws of defamation.

This happened when we least expected it. The regular sketch was called ‘Bones of Your Arts’. It was a parody of those wretched, self-conscious television arts programmes that have long since disappeared. Mark Wright played the lugubrious host and the parody had recently featured Rawiri Paratene as a Maori carver who was trying to create a socket set out of greenstone.

Around that time, New Zealand had purchased two paintings by CF Goldie. There was some discussion among art dealers about the price paid for the works. Some felt it was far too high. Others considered Goldie’s portraits to be important national treasures and heralded the return of the two paintings from the United Kingdom. The arts writer, Hamish Keith, agreed.

Alan, Jon and I decided the price and the value of paintings should be aired on ‘Bones of Your Arts’. I was to play a respected art critic, named Beamish Teeth, who was about to present his latest acquisition to a grateful nation. In the course of the interview it was revealed that I had travelled all over England searching for lost taonga. ‘You visited galleries?’ the interviewer asked.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘Motel rooms.’ My character then triumphantly showed the purchase. It was a well-known and particularly tasteless print commonly known as ‘The Green Chinese Lady’. Naturally, the interviewer was surprised. He became alarmed when my character announced I had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for the print.

So far, so good. Not perhaps knife-between-the-ribs satire, but a light-hearted poke at the pretensions of the art world. Then, my character dropped the bomb. I said the huge price also included my commission.

We did not know that in Auckland art circles, false and scurrilous rumours were circulating that Hamish Keith had received some form of payment for negotiating the purchase of the Goldies. My off-hand remark would be interpreted as a clear reference to those rumours.

Indeed, as was later argued, the mere mention of a commission could be seen as a confirmation of the rumours. Further, it would be hopeless and profoundly stupid to argue there was no connection between a Beamish Teeth and a Hamish Keith.

The shrapnel didn’t start flying for a couple of days. Hamish Keith’s lawyer called the remark a calumny and defamation proceedings began. At first, we were puzzled by the ferocity

of the response but, as we learnt more about the rumours, the unsteadiness of our case became obvious. We could argue truthfully that we knew nothing about the rumours, but it would be difficult to prove.

The meetings started. I remember one vividly. Alan, Jon and I sat with Television New Zealand’s chief counsel, Robert Chambers. Alan idly asked, ‘Do you have a dictionary here?’ Chambers looked up cautiously and nodded. Alan continued. ‘If it was a Chambers dictionary, it would be the Chambers in Chambers’s chambers.’

Robert Chambers stared wildly in my direction, then jumped from his seat and stared out the window for several minutes.

It was a strange feeling continuing to work on a television show while across town in the Auckland High Court both you and your programme were being condemned as vicious slanderers.

Finally, it was my turn to give evidence. I confirmed I knew nothing about the rumours, agreed it would be surprising if an audience didn’t find some similarity between Hamish Keith’s name and the name of my character, and stressed as forcibly as I could that there was no malice towards Mr Keith.

Julian Miles QC rose to cross-examine me. It was like watching a bird of prey emerging from its nest. He was slim, with a prominent nose and glittering eyes. Julian Miles approached the witness box and hovered close to me. He produced a television remote and the sketch started on the screen. I was heartened that some members of the jury laughed when suddenly the screen was frozen. Caught in mid-speech or trapped in an unbecoming grimace, any freeze-frame will make you look ridiculous. I looked positively gruesome.

Julian Miles spoke. ‘I put it to you, Mr McPhail, is that the look of an oily, unctuous man?’ He could make the word ‘Mr’ last for a number of seconds. Julian Miles was clearly trying to show my performance was dripping with malice. I replied that freezing any television programme could create the image of someone oily and unctuous.

Julian Miles now turned to my insistence that I had never heard of the ugly rumours about Hamish Keith. Carefully, he led me through the preparations for the television programme. He suggested I would need to read newspapers and magazines, follow news bulletins and listen to the radio. I agreed. He spun towards me and rasped rapidly, ‘And yet you still expect us to believe you knew nothing about these rumours?’

The only possible reply was ‘Yes.’ I left the witness box perplexed. When required to give evidence in a court you are expected to reply in measured terms so your answers can be recorded. This can create the impression that you are carefully reconstructing your replies and not answering honestly. I was an actor, known for inhabiting characters, and I wondered if the jury believed all they’d seen was a carefully rehearsed performance.

The trial went on. I and my colleagues went back to work.

Finally, the jury returned with their verdict. We had, they determined, defamed Hamish Keith. When asked by the judge what damages should be awarded for this scandalous act, the foreman replied none. This decision did not, in my opinion, sit easily with the judge. He was rumoured to have a dislike of television and the prospect of three outrageous fools not being punished, in their pockets, did not go down well. Months of legal square-dancing followed. There were fights about costs, threats of bankruptcy, even the improbable idea of a charity concert to raise money. I didn’t like this because I had no desire to rely on other people’s charity and, being practical, I believed hardly anyone would turn up. Eventually, it finished.

There are four curious asides to this unhappy affair. While I was giving evidence a woman on the jury winked at me. I still have no idea what that meant. Subsequently, we discovered a Pacific Island member of the jury had only a limited grasp of English.

Moments before recording the ill-fated but still funny sketch, someone pinned a brooch on my lapel. It was a small replica of New Zealand’s iconic Buzzy Bee. Over the years it’s been suggested that it was the brooch, not the mention of a commission, that incited the furious reaction. What has never been explained is why an innocent Buzzy Bee would provoke such anger.

The fourth curious aside is this: I was sitting with my son Matthew at a television awards show somewhere in the grim halls of the past. I looked up and stared directly into the face of Hamish Keith. Our eyes locked and then we both looked away. I toyed with a glass of wine for several minutes.

It has never been my habit to sweep up my blunders and deposit them tidily in the rubbish bin. So, I walked over to Hamish. I spoke of past encounters and how we’d both been bruised. I offered my hand and he took it. The joining of hands did not change what had happened, it simply made that part of our lives possible to forget.

To salve my conscience, I should now relate the strange tale of a monologue. It has only been performed once and my rendition was so panicked and pathetic that the full beauty and utter vulgarity of the sketch never received the international recognition it deserved.

With a group of colleagues, I was performing at an Amnesty International fund-raising concert in Christchurch. A previous concert in Wellington, the year before, had been somewhat shambolic. Some jokes went down like the Titanic. Others were greeted with strained chuckles because the sexual innuendos weren’t actually innuendos. The most memorable performer was John Banas. He was a vital and inventive performer who went to Australia and disappeared.

Banas had perfected a routine that displayed the talent of his pubic hair, responding to military commands. This may sound crazy. It was. But it was performed with such confidence and flair that I laughed and envied him at the same time. John’s pubic hair was represented by a feather-duster protruding between his legs. He had given the bunch of feathers a name. Say, it was ‘Toby’. Banas looked down and in the voice of a sergeant major yelled, ‘Toby, rotate.’ The feather duster began spinning. Banas shouted, ‘Toby, halt.’ The feather duster stopped. ‘Toby, atten-shun.’ It suddenly became erect.

It is hopeless to write about jokes. They exist in an ephemeral moment of their own and I cannot accurately recount the humour of John Banas. Nor can I convey the hysteria caused by Toby and his wild rotations. Laughter arises from surprise and there are few surprises in recollections.

The instructions at the Theatre Royal concert were succinct. Because the organisers suspected many of the bad jokes at Wellington were the products of ill-considered humour or heavily consumed liquor, the performers were not permitted to leave the theatre during the interval between the end of the rehearsal and the start of the performance. This meant there was a lot of time spent waiting in dressing rooms. I was sharing one with Tom Scott and, in an effort to fill the dead hours, we began talking idly about monologues. I don’t recall who raised the proposition that distasteful subjects could be comical if approached with confidence and conviction.

Unfortunately, this led to a search for unmentionable topics and, unhappily, this led on to the subject of paraplegic sex. There was some discussion as to whether this could possibly entertain an audience and we agreed it could. This decision was backed by Jon Gadsby, and a number of fellow performers gleefully waited for the first line to be delivered by a man in a wheelchair.

‘Good evening. I’d like to talk to you tonight about the taboo subject of paraplegic sex. I notice a number of you shifting uncomfortably in your seats. Well, lucky old you.’ First rule of comedy: never pull any punches. So far, so good.

With the noisy assistance from our colleagues, we pressed on. Finally, the monologue was complete. It was a particularly offensive piece but funny if you had a somewhat twisted sense of humour. As most people in the dressing room did.

I thought that having amused ourselves and passed some time the exercise was over. But there was general agreement that the monologue was so outrageously funny and rude it should be performed. After all, where were we? In a theatre with a captive audience arriving at the door.

I kept shaking my head. ‘It’s too over-the-top.’ But, no one agreed. Wasn’t this the ideal chance to prove the theory that any aspect of the human condition can be funny? In desperation

I played my last card. ‘It can’t be done because we haven’t got a wheelchair.’ That was not a problem. A wheelchair would be found. All I needed to do was concentrate on learning the words. As I went over the lines, I had to admit the monologue was comical. If I could just get the audience to agree, I might just carry it off.

The time to find out rapidly approached. Somehow a wheelchair arrived backstage and I started manoeuvring it around. Everyone had agreed that, for maximum impact, I shouldn’t be announced. The appearance of a man in a wheelchair would create a degree of curious expectation in the audience and if I delivered the opening line clearly and buoyantly they would soon find themselves laughing.

I rolled hesitantly onto the stage and as I reached the centre I could feel a sheet of ice forming in the stalls. There was absolute silence in the theatre. Nervously I looked into the wings. Scott and Gadsby were giving me thumbs-up signs. Great, guys. They were off-stage while I was on-stage, right in the middle, staring into a sea of frigid faces.

‘Good evening.’ My voice had gone up an octave. ‘I’d like to talk to you tonight about the taboo subject of paraplegic sex.’ Nothing could be heard except the hint of a sharp intake of breath. ‘I notice a number of you shifting uncomfortably in your seats. Well, lucky old you.’ A deep silence hit me in the face.

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death