- Home

- David McPhail

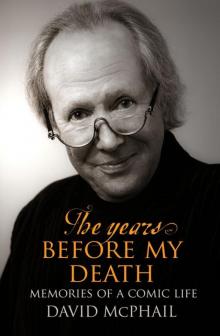

The Years Before My Death Page 16

The Years Before My Death Read online

Page 16

Their presence had caused a flurry with the Feltex organising committee. When I received notification of our nomination I’d requested that the people responsible for the show and their wives should also receive invitations. This was greeted with incredulity. The A Week of It contingent would number nearly 20 people. It had never been the policy of the committee to include such people. All right, none of us will come. The organisers obviously knew something I didn’t because with rude reluctance they agreed.

The programme award was the one we all wanted. Then, to our glee and astonishment, Annie was named the best actress. In the short space of seven weeks she had shown the many layers of her comic ability. Annie had a face that looked through the television camera directly into the eyes of anyone watching. Our delight was increased by the line-up of talented women she’d beaten.

The list of best actors included two principals from Television New Zealand’s million-dollar flop, The Governor. I was up against formidable opposition, so I gave it away and searched for another glass of lukewarm artificial bubbles. When Ilona Rogers said, ‘David McPhail’ I thought I’d drunk too much. I walked through the darkness, stood uneasily on the stage and accepted the heavy award. I had no acceptance speech. I said something that ended with ‘Jeez, Wayne.’ That seemed to work.

It was a good night for us. Our show had come from nowhere and collected three awards. I walked back to where Anne was sitting. We kissed and I began to look rather wide-eyed. The A Week of It crew was much less inhibited. They crashed into the crowd.

Much of the television community seemed as excited as we were, but many were not happy. Some actors were positively sour. A few had staked their careers on television’s supposed triumph The Governor and the show had toppled over. The unhappiness was widespread. A celebrated actress, the late Dame Pat Evison, approached me and in a deep, furry voice said, ‘I congratulate you. But, I regret a real actor didn’t get the award.’ A newspaper critic agreed. He wrote that George Henare and Grant Tilly gave commanding performances in The Governor. ‘These two are streets ahead of anything else I saw — including McPhail’s Muldoon.’ But, I had the two awards in my hands. They didn’t.

The A Week of It crowd was booked into an anonymous motel somewhere on the North Shore. Stern concrete block units set around a swimming pool. We were all slightly over-excited by our success.

We decided to investigate the motel. The first thing we found was a semi-naked Martyn Sanderson playing a primitive flute to a particularly voluptuous young woman. Chris decided he might join them. Around this time someone was thrown in the pool. Chris was urged not to join the flute player and someone else went into the pool. It wasn’t the behaviour you’d expect from 30-year-old adults, but they’d just won three television awards in the face of scepticism and, at times, hostility. So, throw everyone in.

Then, the moment came. Derek Payne was at the same motel. We discovered each other to the sound of someone new being hurled into the pool. Neither Derek nor I was sober. I had the flush that comes with alcohol and becomes exaggerated by excitement. Derek showed the precision he had always demanded of himself. We looked at each other. Together we had broken a barrier — we’d made a New Zealand comedy programme that didn’t sink. But, then I’d made A Week of It and left him behind.

He said it could have been us together on that stage earlier. This was true. I felt so wretched I could only say, ‘Good night’ as another A Week of It writer crashed into the pool.

We returned to Christchurch rather dazed. The small late-night programme we’d regarded as our own was suddenly not. It now belonged to a larger audience and Kevan Moore and his unnamed acolytes were already undermining the flimsy foundations on which it had been built. There was another snag. Stuart Devenie decided to leave. I knew he loved the theatre so I didn’t want to stop him but I was worried the curious chemistry the actors had developed might be damaged. I should not have been so anxious. Russell Smith joined the cast, grabbed a number of roles and captured them.

A Week of It started its second season in 1978 and remained on-air until the end of 1979. This is now a blur. We made the programmes quickly, discarded the scripts immediately and wiped the tapes the morning after they’d been screened.

Hardly anything remains of those two years. The few videotapes that exist of A Week of It are largely incomprehensible to me. Ken’s comments, the sketches and the laughter relate to moments that have long been forgotten. It was, after all, 30 years ago. But, I still look with pride at the rudeness, disrespect and the cheek.

When David Lange first entered Parliament as the member for Mangere, he was a strange figure. He was very large with greasy hair and black spectacles that seemed to be glued to his face. He was a perfect target. The three jokers constantly put the boot into this Mangere airship. After a script meeting, someone suggested getting David Lange down to face our jibes. I wasn’t convinced but telephoned his office. We spoke and he agreed.

So, I flew the member for Mangere down to Christchurch and we all met in a modest restaurant to discuss his appearance on the show. I stress this was a ‘modest’ restaurant. It was so modest there was hardly anything to eat. David Lange was clearly relaxed but as there were no hamburgers on the menu he ate lightly. We talked about how he would appear in the Glue Pot Tavern sketch. He nodded and it was obvious he had other ideas.

Then a curious thing happened. David Lange began to speak of his parliamentary colleagues. He dismissed many of them with withering scorn and well-crafted epithets. He paid particular attention to Bob Tizard, a stalwart of the Labour Party, whom he clearly disliked. Those of us who were at the table with David Lange might have agreed with his sentiments but we became uncomfortable because he had exposed himself so readily. He was sitting in a restaurant with a group of writers who were known for producing unflattering sketches about anyone in New Zealand from the prime minister to Kiri Te Kanawa and yet he was harpooning his own party.

In the years that followed I sometimes wondered if that moment — the sharp mind, the clever words, the need to be accepted or the fervour to be liked — didn’t characterise his life. Years later, after the stomach staples, the crinkly hair and the accountant’s glasses, he yelled at me in an airport, ‘Hey, McPhail. How much do you charge for a speech in Australia?’

I shouted back, ‘I don’t do speeches in Australia.’ He looked back over his shoulder and said, ‘That’s what I thought. So, the market’s mine.’

When he was touring New Zealand we invited Dudley Moore to be on the show. His agent must have been demented because he actually considered it. There was no reason for Dudley Moore to appear in the Glue Pot Tavern. His theatre bookings were good. He didn’t need any further publicity. But, we all admired him and I was delighted when he agreed. His appearance was something of an anti-climax. Moore was charming and friendly but he seemed uncertain about the lines we’d written and didn’t deliver them with much conviction. This is not a criticism. It was difficult to convey to someone who had never seen the sketch, or even heard of the show, the style of comedy we produced. There was no time to let him see a programme and he only had our word that it was popular. Shortly after this we moved away from inviting real people into the Glue Pot. It seemed rather pointless when there was a cast of gifted comedians who could impersonate most people with great accuracy and were a lot funnier. But, the presence of Moore and Lange proved that A Week of It was widening its audience. People rarely agreed to appear on shows that were failing.

Early in 1979, this increasing popularity was confirmed by the television awards. A Week of It was again voted the best light entertainment programme and it received two other awards. I was named the best actor and then, to my astonishment, won the best entertainer award by public vote.

I remember sitting in the audience holding the first two awards when Anne suddenly grabbed my arm and whispered, ‘That camera’s coming around to you again.’ Out of the corner of my eye I saw it focusing on me and then heard my name. This year

my colleagues were much more generous with their congratulations. A Week of It had firmly established itself.

As the year began to close we all started looking at the future. It was unlikely A Week of It would continue into the eighties. There were several reasons. Most of the writers had other jobs. There were lawyers, a journalist, a radio announcer and a novelist. Peter was the author of a best-selling book that had been published in Spain. Any commitment to future television humour or satire would require a major change in a number of lives. Chris, a successful lawyer, was also the father of four small girls. The unpredictability of a life in television was tempting but not really a sensible proposition. Peter was launching a new career as the front man of an enterprising show called Yours for the Asking. (People wrote in asking to see something and Peter, in a genial mood, and with the connivance and skill of Kim Gabara, showed them.) Bruce was keen to stay involved but the demands of print were increasing. Ken was a very successful radio host. He loved his work and truth was you could always make more money in radio than you could in television.

Although A Week of It was highly successful, both actors and writers were still paid ridiculously small amounts. These were the years before people like John Hawkesby. The actors were ready to move as well. Annie had already gone overseas and Peter Rowley was keen to develop his own comedy ideas. It felt it was the right time to finish. I wanted to continue in comedy but I was a salaried producer. There wasn’t the same risk for me. It was Jon and Alan who made the leap into the dark. Alan by leaving the law to become a full-time writer and Jon by committing himself to Christchurch and a comedy future with me.

I stood in the empty Civic Theatre after the last show had been recorded. It had been a tempestuous three years. Together we had all created an idea that revealed New Zealanders would consistently laugh at their own television comedy. They were the three best years of my television life and I didn’t really want them to end. The future looked promising but, like everything in television, it was uncertain. I walked out of the theatre and slammed the door. It echoed for several seconds. I didn’t know if this was a good omen or a bad one.

Chapter 15

A DEEP AND FUNNY FRIENDSHIP

McPhail and Gadsby got its name not because we were narcissistic but because nobody could think of anything else. As plans were laid for the new programme many names were tossed around but they all seemed either dull or unrealistic. ‘A Laugh a Minute’ for instance would be leading with your chin. But, over time, the technical and design staff needed a name as bookings were made and materials for costumes and sets were purchased. Everyone simply described it as the McPhail and Gadsby show. We were approaching the deadline for the first programme and a title sequence was being designed. Someone made the decision. ‘Look, we can’t muck around any longer. Let’s just call it “McPhail and Gadsby” and be done with it.’

The plan for the new show was quite simple. Jon and I would play most of the roles backed by actors hired for each episode. Writers from A Week of It would contribute sketches but the programme would shift away from weekly topicality. It would become more general and instead of being 24 minutes long it would be extended to 48 minutes. The last two decisions nearly caused a disaster. Jon and I were concerned, perhaps too concerned, that this new project should not be confused with A Week of It. It should have the irreverent flavour of the previous programme, but it should be seen as something new.

So we strived to be both different and the same. This was impossible. Then, we shot ourselves firmly in our feet by deciding each episode would concentrate on only one topic. We agreed the topics would include religion, sex and death. On paper this would look like comic suicide, but we and the writers were carrying the idea around in our heads, where it made perfect sense.

We began work on the first show — Religion. As was the pattern with sketch comedy you wrote and recorded the exterior sketches first. One of the early ones featured me as an imperious pharaoh and Jon as the mother of the baby Moses. The infant was placed in a reed basket that promptly sank. So far, so good. Another sketch opened with the children of Israel rushing to the sea to escape pharaoh’s chariots. Jon, as a rather naive adult Moses, thrust forth his rod in the expectation the waters would part.

Then, following God’s command, he strode into the sea commanding his followers to do the same. We shot this on New Brighton beach. Moses kept walking out into the waves screeching to the Israelites that he should be followed. Finally, he disappeared under the waves, still yelling. The Israelites shrugged their shoulders and went home. (Have you noticed any similarity between those two sketches? They both involve drowning.)

There was one long and involved piece with me as Adam and Jon as the voice of God. It became almost impossible to record because of a helicopter circling constantly overhead. I was wearing nothing but a small pair of underpants and a Velcro fig leaf. I was getting very cold when a crowd of Japanese tourists walked past. The sight of a man in underpants screaming at a helicopter was their introduction to New Zealand culture.

Later Jon and I were filming two sketches on location and needed to change our costumes. The production had no money for caravans and we were advised we could change in a male public lavatory close by. We didn’t have time to object. Jon and I rushed in, stripped off our costumes and were standing in our underwear when an innocent bystander walked in. He recognised us immediately, gave one look of astonishment, said, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake,’ and scrambled out. I sometimes wondered what he told his wife when he got home.

The religion show was coming together. It looked promising and it was new territory. This made it exciting. There was a balance between the sacrilegious and downright silly and I thought Alan, Jon and I had managed to maintain a standard of humour. The first episode of McPhail and Gadsby screened in the middle of 1980. It was greeted with astonishment and, I suspect, not just a little disappointment. The show was certainly different from A Week of It, but the difference was so great that many in the audience couldn’t understand what they were watching. Where was the satire and where were the political jibes? Why wasn’t McPhail doing his Muldoon impersonation and what happened to Gadsby’s Wayne character? Instead they were given 48 minutes of disrespectful and sometimes insolent jokes about Christianity and the Bible. All the sketches were within the limits of what we thought was legitimate vicar-bashing, and then one jumped the fence and crossed the boundary into what most religious people call blasphemy. It was a simple, almost secondary sketch that, in spite of my religious upbringing, didn’t raise even a flicker of unease in my mind.

It went like this: an Anglican vicar, Gadsby, was dispensing communion. He passed the chalice to a member of the congregation. It’s important to remember that at that moment the devout believe the chalice is symbolically filled with the blood of Christ. So, I savoured it for a second or two and then asked the vicar, ‘You wouldn’t by any chance have a Chablis?’ At that moment, the rafters fell in.

Until then, my name and address had always been in the telephone book. I’d never had any reason to remove them. In fact, I had a certain pride that I could be thumping politicians over the head, but you could still telephone me if you felt like it.

Everything changed after the religious programme. The abuse started with my children. They had been taught to answer the telephone briefly and courteously. ‘Hello, this Matthew McPhail.’ The vitriol was palpable. I saw Anna’s face turn white during one call. I wrenched the receiver from her hand and heard crude and loutish language before I slammed it down and rushed to hold her.

The Christians kept it up for four days until I changed the number. These events confirmed my distaste for people who might bless a child one day and then scream obscenities at her 24 hours later. When I was part of the Christian faith my belief was absolute and immovable. The disdain or disrespect of other people meant nothing to me. They could taunt or laugh at me, even humiliate me, but it didn’t matter because I was secure in the love of God and the power of the ris

en Christ.

But, what was the nature of beliefs that were so easily splintered by a short and silly sketch on an increasingly unpopular television show? Were they beliefs at all? Was God’s grace really affronted by two comedians dressed as nuns singing:

Frankly, St Fred’s is not a happy convent,

It’s a disgrace to nunning, I agreed.

People are talking all around the parish,

Honestly, things aren’t what they used to be.

Mother Superior’s really gone demented,

Lately, she makes you wonder where you are,

Wearing those see-through frocks,

And hanging around the docks,

I think that’s taking charity too far.

Or was a devout faith in Christianity really shattered by two increasingly stroppy angels learning of God’s intention to create heaven and earth?

Gabriel: Have you seen this week’s job sheet?

Michael: No. What has the divine architect got up His infinite sleeve?

Gabriel: Creation of Heaven and Earth, mate!

Michael: He’s not!

Gabriel: He has! Here in black and white — ‘creation of the heavens, earth, oceans, continents, firmaments and all the creatures what dwell therein.’

Michael: What dwell therein?

Gabriel: Yeah, grammar was never his strong point.

Michael: He’s not serious?

Gabriel: Have you ever seen Him laugh?

Michael: But, but …

Gabriel: And do you know what’s worse?

Michael: What?

Gabriel: We’ve got six days to do it in.

Michael: Six days? What does He think I am — a bloody miracle worker?

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death