- Home

- David McPhail

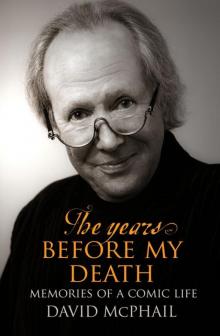

The Years Before My Death Page 14

The Years Before My Death Read online

Page 14

The lack of funds created another set of circumstances I never imagined. My role in Something To Look Forward To had always been ambiguous. I was a salaried television producer working full-time for a network. Yet, for about ten weeks I was employed solely as a script writer and actor. It seemed a little odd but I always believed that if you had any talent you should use it and, while I considered myself a competent and efficient producer, I sensed I was a better writer and performer. With the same incomprehensible logic I applied to my relationship with Derek, I decided this anomaly could be ‘sorted out’ at a later date.

While preparing for the pilot I became increasingly aware the limited budget was imposing serious constraints on the project. My main concerns were the amount of money I could pay writers and the number of actors I could employ. In the end I decided to play some roles myself and asked a fellow producer, Bill Mackie, to direct those sketches. By this time a loose team of writers and performers was assembled.

When I first started planning the show I had looked to Wellington as a likely source of contributors. I knew the names Roger Hall and Joe Mustaphia, and while the writers of In View of the Circumstances had not overly impressed me, at least they had some experience. I persisted in this approach until someone asked the obvious question: ‘What about the people you know in Christchurch, particularly the guys you worked with on the Merely Players show?’ I don’t know why such a sensible solution had escaped me. I knew Chris McVeigh and AK Grant. Ken Ellis was one of my closest friends as was Bruce Ansley. Peter Hawes made me laugh. And there was Jon Gadsby.

I’d met Jon at a party in Dunedin some months before. At the time I was directing the recording of a concert by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and was invited to meet a man who was said to be ‘very funny’. This is an unwise thing to say to someone who also thinks he’s very funny. Gadsby and I stalked around the party for half an hour taunting each other to raise a laugh.

Five hours later at 4 am we were sitting in his dilapidated van still laughing. Later we infuriated residents of Dunedin by playing ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ over and over again at a mind-spinning volume. I had, by a lucky chance, bumped into a man with a fertile comic mind whose humour made me laugh and who understood my jokes.

That evening would define the next 20 years of my life.

Slowly, the pilot took shape. It was a motley creature: a bare minimum of costumes and props, elementary lighting and one piano. There were only two things that could persuade the sceptical chiefs — the script and the performances.

I remember little of the week leading up to the recording. Although I had directed snippets of sketches in the past, this process was new to me. There were no rules and the methods we devised for producing the show seemed to make the task more difficult. The schedule created for making the pilot would be the template for a series: if the programme was to be played on a Saturday, it would be recorded on the Saturday in front of an audience. I always wanted to perform A Week of It live, but the executives were adamant it must be recorded. I don’t think they trusted me.

In the end it made little difference. We recorded the programme only an hour-and-a-half before it was played, so it had to be performed as if it was live. This meant there were very few chances for second takes which imposed an added strain on the actors and the crew. To achieve the topicality for a Saturday show, work on writing the scripts didn’t start until the Wednesday before and lines were constantly changed or updated. This put a great deal of stress on the writers. Then, the short time between the creation of the script and the need to record it increased the pressure on the designers, builders and technical crews.

I seemed to be introducing so many demands that the show would prove impossible to make. Unfortunately, the pilot no longer exists, much like most of the A Week of It shows. The administration remained insistent we reused videotapes, so the moment a programme was screened it was wiped. I tried frequently to hoard shows in my office only to receive a curt note demanding I clear out all existing videotapes. So there’s no way of finding out why, to my delight and astonishment, the executives decided a series of A Week of It could be made based on the pilot.

It was made clear to me that there was to be only one series of seven programmes. Any thoughts I might have about further shows should be dismissed immediately. Oh, and incidentally they decided to screen it at 10.10 pm. In the seventies only insomniac vampires watched television at that time. But the approval had arrived although I did not altogether believe the telephone call. Then, as now, television was ruled by duplicitous phone calls and false assurances. I asked if a telegram could be sent confirming the decision.

When we received the telegram, Anne mounted it on a tray of foil and we displayed it on the mantelpiece of our house. Then we had a rowdy party with the actors and writers. It is difficult to explain how important this decision was for us. We all had other jobs and ambitions but the possibility of this programme had become an insistent part of our lives. I thought we were better than any other comedy outfit in the country. I excluded John Clarke because his individual brilliance could never be imitated or exceeded. But, in the small, rapidly diminishing community of New Zealand comedy, we were the best. The first series of A Week of It was our one chance to prove it.

Immediately there was another problem. I acted in the pilot to save money and to allow me to pay the other actors slightly more than a bus fare. The question arose about my on-screen role in the new series. I had not seriously considered appearing any further, but it became apparent there were certain roles that suited my face and stature: one in particular arising from my slight resemblance to the then prime minister, Robert Muldoon. A new formula was hammered out. I could produce the show, write for it and act. But, obviously, I couldn’t direct as well. A new director had to be found. At that time most directors were also producers and naturally would feel unhappy about relinquishing one job just for the fun of working with David McPhail. After a lot of discussion and a degree of reluctance from the head of entertainment, I convinced them all that a young man would be perfect for the job. He had previously been a cameraman and a floor manager but had lately moved into direction. His name was Tony Holden. This marked the start of a relationship that has waxed, waned, then waxed again for more than 30 years.

There was a little more shuffling as the series developed. Jon Gadsby would commute from Dunedin to work on the show and stay with Anne and me in Matthew’s bedroom, which was the size of a renovated shoe-box. Annie Whittle joined the group. Then, from Tony Holden, I got the name of a stage manager at The Court Theatre whom Tony described as very clever. I wasn’t sure about Peter Rowley when I first met him, but his audition showed he was a skilful mimic capable of a huge variety of voices as well as a formidable collection of sound effects ranging from a submarine submerging to an Iroquois helicopter strafing a paddy-field. According to Peter, when I telephoned to offer him the job, he put his hand over the receiver, punched his other hand in the air and whispered, ‘Yes!’ Then he returned his mouth to the receiver and in a somewhat disinterested voice said he’d need a moment to think about it.

There was one other actor I particularly wanted: Stuart Devenie. Even back then, Stuart had a formidable reputation and I knew he was a gifted comic. I had no money to put him up so he boarded with Chris McVeigh and his family.

In spite of the illusions created by television and the air of affluence, actual programmes were made by well-trained, talented and severely underpaid handymen.

The writing team was well-established. Alan (AK Grant) and Chris wrote together and sometimes Jon and I teamed up. Peter Hawes produced wonderfully incandescent and sometimes, frankly, lunatic sketches. Ken Ellis provided a cascade of ideas and Bruce Ansley had the unenviable job of writing the last-minute script that linked the sketches together.

Early in the series the team included Endel Lust, who’d worked with Chris and Alan before and would later take a lead role in Kim Gabara’s wacky children’s show A Hauntin

g We Will Go. Somehow, Endel’s sense of humour and mine didn’t connect. I was striving for a group of writers who were fast, prolific and not married to their scripts. I also wanted a team where healthy disagreement was possible and didn’t lead to dissent. It was with some difficulty I asked Endel to leave the programme.

Elsewhere a production group was being formed. The speed required for producing A Week of It was daunting. As many as 18 different set-ups might be needed in a show and the technical producers and designers didn’t see the scripts until less than 48 hours before the programme was recorded. Two important design decisions were made early in the planning. We would build a circular, rotating platform on the stage of the Civic Theatre. This would be divided into three sections, rather like a round of cheese, and would give us three separate acting areas. The other decision was to dispense with realistic sets. Any new location would be represented by a flat, painted, simple cartoon. It was cheap and fast and looked rather primitive, although whenever anyone criticised the set, I always replied it was the programme’s trademark style. ‘Newspapers have cartoons. We are television’s cartoon.’

Tony designed and created the titles. A globe spun erratically and creaked open. The programme’s name was then typed incorrectly in the empty space. Several corrections were attempted and finally the right spelling appeared. It looked a little shonky but it worked. As the night of the first programme approached we spent two weeks practising with ‘dummy’ shows. We would follow the schedule, writing sketches within the time allowed, holding production meetings to judge our ability to prepare the sets and props, and rehearsing the show as if we were really going on air at the end of the night. The system was stretched but it held. We were due to launch the first show on Monday night, 4 July. To commemorate American Independence Day Tony filmed a complicated sketch involving a woman tied to a barrel of dynamite while an inept back-woodsman, played with great empathy by Peter Rowley, and his sidekick — me — fruitlessly tried to shoot out the fizzing wick.

What this had to do with New Zealand current affairs still escapes me. The show also included an appearance by the prime minister. I was filmed as a young Robert Muldoon crouching beside a fallen tree, holding a small axe in my hand.

A loud male voice then started to speak and I quickly hid the axe behind my back. The voice asked: ‘Robert Muldoon, did you cut down that cherry tree?’ I replied, ‘I cannot tell a lie, Daddy. Teach me.’

A Week of It was the first comedy to contain impersonations of real New Zealanders and the first to blatantly deride politicians. In the opening programme we asked the question: ‘What is Bill Rowling (the leader of the Labour Party at the time) like in bed?’ We then revealed a photograph of Bill Rowling lying in a bed.

We backed this up with the information that we had evidence of Robert Muldoon getting a lay. To prove it we showed a real photograph of the prime minister receiving a lei from a blushing Hawai’ian dancer. In a subsequent programme Ken proudly announced we had discovered the prime minister’s family tree and up came a picture of a silver birch. Ken explained: ‘This proves Robert Muldoon is the son of a birch.’ So, as we approached 4 July, we were excited, nervous, cocky and stricken with doubt all at the same time.

The executives at South Pacific Television suddenly woke to the fact that A Week of It was about to go on-air and they had no idea what the programme would contain. A hasty meeting was called to establish the procedures needed for censoring the script or ‘overseeing the content’. I was opposed to this.

Most of us knew about the laws of libel. I started my diminutive career as a newspaper reporter. Bruce was a journalist and columnist. Ken hosted a successful radio show and was already doing edgy and ribald raves about New Zealand life. Chris and Alan were lawyers. Jon was within two units of an LLB. Peter Hawes had no observable legal qualifications, but I thought we could keep him in check. I knew this was sufficient protection from possible litigation.

But the possibility of legal reactions to the show had not entered the minds of my superiors. They were more concerned with questions of taste. Would a particular sketch offend the sensibility of viewers? Did these lines jump the vague barrier between acceptable comment and bad taste? Was it proper to call the prime minister ‘the son of a birch’?

The answers were arbitrary. No one had defined the barrier between good and bad taste because few television programmes had come within 500 metres of approaching it. Was it proper to call the prime minister the son of a birch? Yes.

Finally, with reluctance, I agreed the scripts should be shown to the Christchurch station manager for final approval. I had little confidence in this arrangement. I doubted the comic acumen of the station manager. He may have been a man who made worthy documentaries, but might not recognise a joke if it bit him on the knee.

As time went on we developed a simple system for gaining approval. We would occasionally write an offensive sketch that we had no intention of using. Usually placed underneath it was the offensive sketch we wanted to play.

I would be summoned to the manager’s office to justify the wanton material I planned to inflict on unsuspecting families. Summoning up my best comic abilities, I argued that to remove the sketch would be a gross violation of public speech and we had a duty to uphold the freedom of expression. The manager would be unequivocal. The sketch was out. I’d then ask if there was anything else that was doubtful. He’d reply there wasn’t and the sketch we wanted got into the show.

This system wasn’t in place on the night of the first programme. We intended to open with a blast that would show this programme wasn’t coming from the safe suburbs of Christchurch. Jon sat behind a news reader’s desk in a black singlet with a yellow towel around his neck. (Is this familiar? Does it remind you of Billy T James six years later?) Jon looked into the camera and said, ‘Now, the news in Maori. But first — he paused — here are the scratchings from Te Rapa.’

There was a flurry of telephone calls. We were all engrossed in getting this new and difficult show together. But, a decision had been made in the echoing halls of South Pacific Television. The Maori News sketch had to go.

I always knew there would be editorial differences. A Week of It moved very quickly. A sketch that was part of the show in the morning would have disappeared after lunch. But, to have the leading sketch in the first programme axed only hours before it was to be screened was something I hadn’t anticipated.

There was no time to write a new sketch. The replacement had to use the same set, with the same costume and the same actor. We hadn’t been on-air once and already we were running out of time.

This was the first thing we showed a small, but expectant, audience: Jon sat in the news reader’s set and announced, ‘A rare white heron or Kotuku was seen today wading in the Christchurch settling ponds. Unfortunately, our cameraman couldn’t get there, but it looked like this.’ He then twisted his body, waved his arms above his head and started emitting high-pitched, bird-like shrieks. Jon did his best but, if I’d not wanted to watch the rest of the show, I’d have turned the television off and gone to bed.

We all looked at the first episode with a combination of delight and despair. There were many sketches that worked and the show had the dissolute roughness I wanted. It didn’t look like the trim, twinkling productions from Auckland or Wellington. Although it was recorded, it felt like live television. There were visual blemishes, sound drop-outs and fluffed lines but it leapt at the audience like a wilful, frivolous, raucous piece of fun.

Recording in front of an audience caused its own problems. They could not be expected to sit for long periods of time and not be entertained. Precious time was lost as they filed into the theatre and found their seats. But, as we were all jumping into the realm of the unknown they made a vital contribution to the show. The audience was a litmus test for our sketches and gave us advance warning of the weak spots. Not that this was particularly useful because, if a sketch died, there was no time to edit it out. But, at least we had some imp

ression of how the television audience would react and this diluted the disappointment when we sometimes misfired.

I soon decided that as we were showing the audience on-screen to prove we weren’t playing recorded laughter, we should make more use of them. So, we established the practice of zooming in on individual members and inserting facetious captions under their faces. Such witticisms as ‘Doesn’t know he’s left his car lights on.’ And ‘Has stroked the Royal corgis.’ After a while we stopped doing that.

The speed with which A Week of It was recorded created some bizarre moments on-screen. In one sketch, Chris, Peter, Jon and I were all dressed as lawyers. As the dialogue progressed it must have become increasingly apparent even to a casual viewer that none of us knew who had the next line.

A number of non sequiturs were exchanged and increasingly the sketch sounded like nonsense. Suddenly Chris blurted out a line, looks of utter relief flashed across our faces and we finished the sketch at break-neck speed. A few days later a friend who had watched the show mentioned the sketch and asked, ‘What the hell was that all about?’

During another recording Peter got a mental block on a report to the camera. We never used auto cues or word prompting devices so all speeches had to be delivered directly to the cold, unflinching eye of the camera. Peter had to say, ‘Tonight, we investigate the vexed question of Maori land. Vexed because it is, Maori because it’s not and question because it isn’t anymore.’ Try as he might he couldn’t complete the sentence and this naturally made him more and more frustrated. Although time was short, I decided to give Peter five or six minutes to straighten out before making a final assault on the speech. After the break he started again and this time flew through it perfectly. The audience responded with an outburst of claps and cheers. This must have puzzled the viewers at home because what Peter said wasn’t all that funny.

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death