- Home

- David McPhail

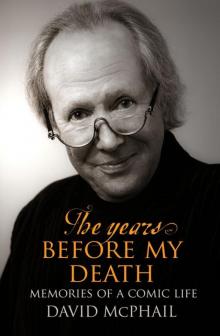

The Years Before My Death Page 11

The Years Before My Death Read online

Page 11

At the Queen Mary Hospital fathers were confined to a small waiting room with a pot plant for company. Husbands were permitted to smoke a cigar when notified of a birth but they had to remain in the waiting room until requested. Anne McPhail did not agree with this.

She spoke to the obstetrician about my being present and he agreed and then convinced the hospital’s matron and some of the staff. They were not particularly congenial. I was happy not to be part of the negotiations. I didn’t know the matron but I knew Anne. The matron had trained many young women like Anne. Bonneted and flat-bosomed, she had taught them the use of bedpans, how to make hospital corners with sheets and endless ways of starching a uniform or laying out a dead patient. But, she’d never confronted this staff nurse about to have her first baby.

There was a formal letter and much discussion. Finally, we received the reluctant approval allowing me to attend the birth. I was the first husband allowed to watch the birth of his child at Queen Mary.

I rushed around preparing for the dash to the hospital. Anne didn’t rush. In fact, she told me to stop panicking. Her response to the contractions was as calm as mine was hysterical.

We were in a surgical room with lots of white sheets. Anne’s labour was long, hard and loud. Once a nurse ordered, ‘Push’, and Anne replied, ‘What the hell do you think I’m doing?’

Suddenly, they swept Anne through a set of swinging doors. I was in an anteroom staring hopelessly at the linoleum when a chisel-faced nurse entered. I explained rather diffidently that I should be with my wife. She gave me a withering look, threw me a bundle of clothing and said, ‘Put these on.’ It was a surgical hair-net, surgical trousers, paper galoshes to put over my shoes and a white gown that tied at the back. I could hear my wife giving birth to our first child in an explosion of expletives, so I hurriedly donned the costume.

The shoes, the hair-net and the trousers were easy. But the gown needed to be tied at the back. I have difficulty tying my shoelaces when they’re in front of me. Knotting a surgical gown behind my back was like trying to eat jelly with chopsticks. It couldn’t be done. I contrived to keep the gown in place holding my shoulders back rigidly and pushed through the swing doors. No one paid any attention to me.

I sidled up to the bed, grabbed Anne’s hand and announced rather melodramatically, ‘Don’t worry, darling. I’m here now.’

She turned to me and began to giggle. ‘You look like a pastry cook.’ Then, a contraction turned her laugh to a groan.

I have always believed there are certain emotions that are specific to a particular event. The sight of my child being born produced a sensation in me that I had never felt before and would feel again only once more when our son was born.

Our first baby was small and dark-haired. Anne held her for a moment and then the obstetrician, Mr Sidey — we never called him anything else — immediately whisked Anna to a tilted board and began examining her. Apart from the baby’s whimpers the room was silent. For some reason I decided to fill the silence with some conversation. I looked over Mr Sidey’s shoulder and said, ‘I understand at this moment babies actually see upside down and have to learn to reverse the image.’ I had no idea where this nonsense came from and the moment I said it, felt like an idiot.

Mr Sidey saved the day. He continued examining our baby and replied, softly without looking at me, ‘Is that right? I don’t think they taught me that at medical school.’

I hastened back to Anne’s side. Clearly I wasn’t needed at the examination.

As many couples discover, nothing can really prepare you for being parents. We’d chosen the name Anna for our baby. It seemed to suit her. But, she was still something of a stranger to us even though I had written to her before she was born.

I have put a picture on your wall,

A grand and red-faced cat.

A pleasant cat to welcome you,

Whoever you are.

I hope you like cats and smiles

And gentle things

Like butterfly wings

And the inside of roses.

I hope you like me.

Anne was much more practical than me and took on the role of motherhood in a business-like manner. There were still moments that baffled us both but the book that saved us was published by the Plunket Society. The author was Dr Neil Begg. His advice was clear, concise and down to earth. I recall two of Dr Begg’s instructions that, while they didn’t apply to Anna, always made me smile. He was addressing the problem of a young child sleep walking. Dr Begg’s solution was simplicity itself. He advised putting socks on the child’s feet and dropping a few small pebbles in the socks. He confidently predicted that once the sleeping child’s feet hit the floor, the pebbles would make them jump back into bed. Dr Begg’s advice in dealing with fractious children who held their breath was even more succinct. ‘Let them,’ he wrote. They will eventually turn blue in the face and may even pass out, in which case the body’s automatic functions will take over. Do not, he stressed, ever become anxious.

Twenty-one months after Anna’s birth our son arrived. Matthew was a broad, sparkling boy with a wide smile and very active arms and legs. He grew up to have wild, curly blonde hair. Today if you place an early picture of Matthew beside a recent photograph of his son, Milo, they are nearly identical. My love for my children has been unending. Through all the storms of adolescence it was constant. I was puzzled and frightened by Anna when she became a Goth, but relieved when I heard her laugh at herself. When Matthew left home at 18 to live and work in Auckland, my only instruction was ‘Never sleep in your car.’ When I walked into his empty bedroom after he left, my response was:

At the beginning of the morning,

And unlike any other morning’s dawning,

(You see, I strain to find a Manley Hopkins’ rhyme

And capture it without shame)

I hope for some Xanadu

Or a cloud of painted daffodils

Or even a bridge cross a silvery Tay

To erase the minutes of this day

To keep the raven’s wings at bay

And paralyse the words that say

My son is leaving.

But all these long and cruel months

And tigers burning bright

Or wretched moths in their hypnotic flight,

All the wedding guests weaving

By the widow-bobbing sea,

All the darling buds of May

Will not change a second of the day

My son is leaving.

The bows of burning gold

The black beasts of the chapel fold,

Songs of light, discarded

Words that leave you cold.

When I was young and ringing with the chimes

There was no sunless sea,

No root of dank despair.

April may be a cruel month,

But February is too cruel to rhyme

Because it marks the time

My son is leaving.

So, all my life dashes down

To a single changeless moment.

An empty room in a long house.

There are no rhymes,

But every wall is singing of my son

And his leaving.

My children had an unpredictable upbringing. They lived with a loving mother and a devoted, if occasionally distracted, father. In later life, the house was always filled with unusual events. Members of the Royal New Zealand Ballet might appear. One Sunday afternoon a classical group spent four hours trying to get in tune. There were large and noisy parties. One evening when the children were safely asleep a burglar ransacked our bedroom and no one heard him. He could have set off a landmine in the hallway and we wouldn’t have noticed. Some years later Anna, her remarkable cousin, Jonathan, and I were listening to Pavarotti at two hundred thousand decibels when I noticed a thumping that seemed to be out of time with the music. I opened the front door and in front of me were three police officers and a noise abatement officer. A

constable shouted, ‘We’re here to close this party down.’

I thought he was demented. ‘What party?’ I yelled back.

‘This party, you idiot,’ he roared.

‘There is no party. My wife is asleep. My daughter, nephew and I are just listening to the world’s greatest tenor. So what’s the problem?’ I replied.

The police officer turned back to his associates and conducted a muffled conversation. When he swung back he pushed his face very close to mine. He was wearing Old Spice aftershave. ‘If you don’t turn that music down immediately we will confiscate every piece of musical equipment in this house and you will be subject to a heavy fine.’

I thought it was a reasonable request and resisted the impulse to crack a joke — they weren’t a good audience. They turned to leave and then the noise abatement man thrust a piece of paper and pen into my hand. He said, ‘Dave, could you give me your autograph?’

The following morning I discovered the next-door neighbour had hurled a field tile through a sunroom window. I hadn’t even heard the glass break.

We sometimes discussed the oddness of our life with our children. Foolishly I tried to make it seem normal. I would say that some children’s fathers were plumbers and some were lawyers and I was simply an actor. There was really no difference. It was Matthew who saw through this charade. ‘But plumbers and lawyers don’t do it on national television, do they?’

Chapter 12

NEW TIMES, TERRORS AND ODD PEOPLE

After three years, three houses and two children, Anne and I returned to Christchurch and I became the producer of The South Tonight, a local magazine-style television show. The two stars of the show were Rodney Bryant and Bryan Allpress. They were disparate personalities. Rodney was large and ebullient, with a loud and penetrating voice. Bryan, a former naval officer, was reserved, precise, and spoke with a clipped, sometimes arched, conversational style. Although, this didn’t stop him hurling a typewriter across a newsroom when enraged by a petty squabble.

On screen, they connected like gleeful brothers and they became the most successful duo on Christchurch television. Rodney decided we should produce a survey of the city’s pies. This gave me reason to remember the old pie man at the Gresham years before.

According to Rodney, we would rank them on their taste, texture and then, with the assistance of the Department of Health, analyse their nutritional value. We purchased 12 pies and subjected them to scrutiny. The pie that came in at the bottom of our list was a Margareta — the same pie I had devoured with such enthusiasm at the Gresham. Ken Ellis and I loved those pies. They were juicy and tasty and seemed to contain enough protein to last us a week. I was surprised and disappointed they rated so poorly. That might have been the end of it, except Rodney, in a moment of heightened liveliness, accidentally knocked the Margareta pie off the table and onto the floor. We were broadcasting live so there was no chance to edit or re-record our survey.

What we transmitted looked remarkably like Rodney dismissing the lowly pie with a contemptuous sweep of his hand. The following day the legal telephone calls started. In later life, I developed a technique for dealing with letters from outraged lawyers. I threw them in the rubbish bin. When a second letter arrived, I tossed that in the rubbish bin as well. But, these were early days and a hand-delivered letter from an obstreperous solicitor caused alarm.

The head of news in Christchurch, a small, benign man named Buzz Harte, called me into his office. He’d watched a recording of the pie incident and felt the complaint was justified. I argued that the solicitor in question was a dogmatic and strident critic of television and had probably approached the pie company to suggest starting proceedings. Harte, who was somewhat dubious about me, suggested, in the gentlest way, that I pull my head in.

The NZBC paid $6000 to the makers of Margareta pies. Back in the early seventies, this was a huge amount. I was chastised and the pie company prospered for another 15 years. Such was the damage Rodney and I caused to its reputation.

To be fair to Buzz Harte, I had adopted a rather extreme appearance at this time. My hair was long and, although clean, unkempt. I was wearing a purple bomber-jacket over black and white trousers and I stood in black shoes with dangerously high heels. It must have been difficult to take me seriously.

Rodney and Bryan had a heady partnership. The South Tonight was widely watched mainly because of their distinct and colourful eccentricities. It seems strange now, in an age of pre-packaged personalities with carefully attached smiles, that two men could command attention simply by being themselves. Eighty per cent of the Christchurch audience watched them, not always for what they were saying, but how they said it.

With them, I managed to combine sensible current affairs with a frivolous disregard for reality. In a parody of a British documentary called The Source of the Nile, we found the source of the Avon River. It was a leaking tap in a garden on the edge of the city. Another week, we invited those watching to save electric power by turning off one appliance in the next half hour. This act reduced power consumption by 30 per cent.

There was an underground men’s lavatory in Cathedral Square. It had long been closed, when the city council for some reason decided to reopen it. No ceremony was planned, city councillors feeling more comfortable cutting ribbons at crèches than unlocking public lavatories, so we created one. I hired a brass band, bought banners and bunting and staged a ceremonial procession headed by Rodney and Bryan. My finest moment was when they approached the gleaming urinal and adjusted their trousers, I cut to a shot of a champagne bottle popping.

There is a curious aside about this once historic lavatory. My memory comes from a time when a small boy like me would go to a public lavatory as naturally as he’d climb a tree. It was lined with white tiles and the urinals were huge aluminium columns shaped like juke-boxes. The underground latrine, as it was coyly called, had a permanent caretaker. He was a moon-faced man who avoided eye contact. He was said to be the scion of a prominent land-owning Canterbury family and he had been a Rhodes Scholar. But then something nasty had happened. What it was no one had the courage, or probably the knowledge, to say. But, I was assured it had happened and that was why he was cleaning a lavatory under Cathedral Square. It was a gothic story that appealed to my imagination, but later I judged it as a rather clumsy warning to behave myself.

During the time I produced The South Tonight my genial nemesis was Bob Clark. He was a friendly, broad-faced journalist with a deep drawl and a powerful respect for the integrity of current affairs. Bob was responsible for the news content of the programme and my leaps into absurdity did not sit well with a man who wanted more stories about local body budgets. Had I not started my working life as a journalist, Bob might have talked me down. But, he had to accept that painful concession. Bob often lamented, ‘I don’t know why we’re doing this.’ We would sit opposite each other every morning and exchange thoughts about what should be in the programme that night. There was a lot of negotiation and some arguments. Had I not conceded to Bob the importance of filming the resurfacing of Colombo Street, we would never have opened an underground lavatory in Cathedral Square.

Rodney and Bryan were a potent duo and it still surprises me what television rejected. A sensible person would have seen the powerful attraction of these two local heroes and made some attempt to use them in another role. Instead, they were discarded by men who saw the television audience as a willing flock of geese who would be happy with anything thrown in their direction. Rodney attempted a revival on network television but his voluble presence sometimes unsettled the people he was interviewing. He left television, shifted south and began working for the Dunedin City Council. He’s still there, broad and buoyant as ever, with eyebrows as surreal as Salvador Dali’s moustache and roughly the same shape.

As for Bryan, I don’t know what happened to him. The man with the most hypnotic eyes on television never seemed fully at ease. He could be introspective one moment and wildly turbulent the next. He ac

cepted the momentary fame with discomfort and shied away from public admiration.

It is important to place The South Tonight, in fact all television of the seventies, in the context of its time. It was still the wretched relative of radio. Anyone who appeared on television was paid a wage that was meagre. The performing staff were constrained by a set of intractable regulations designed to make them meek public servants and to ensure their equality with fellow workers. A resonant blast of originality was greeted with doubt and suspicion. Bryan’s unmatched skill was an ability to communicate directly with individual members of the audience. I admired him tremendously, but I never knew him well. I don’t think that was permitted. Bryan remains the most enigmatic person I ever worked with in television.

This was a defiant time for me as I sat in an old, familiar newsroom and watched reporters who were total strangers. Three years earlier, Anne and I had been dispatched to Dunedin for me to make the type of television I despised. Now, we were back in Christchurch with two small children. We needed to re-establish our life.

It was good to be on home ground. There were two grandmothers who didn’t need to travel a perilous road or buy an expensive air ticket to see their grandchildren. Nor did they need to visit the unpredictable world of Dunedin. This was where the normally sensible Anne and David filled balloons with helium, tied 30 around the garden to brighten a dark winter’s day, then cut them loose and watched as the balloons drifted over Dunedin — a delight to behold and a danger to low-flying aircraft. We had survived and now we had to get on.

The distinguished director, Elric Hooper, told me most theatrical memoirs consisted almost entirely of name-dropping. He was right because I’m about to do exactly that by quoting him. The bag of names I can drop is quite small and, considering I have worked for nearly 40 years in the entertainment and music industry, it is not particularly impressive.

The Years Before My Death

The Years Before My Death